Introduction

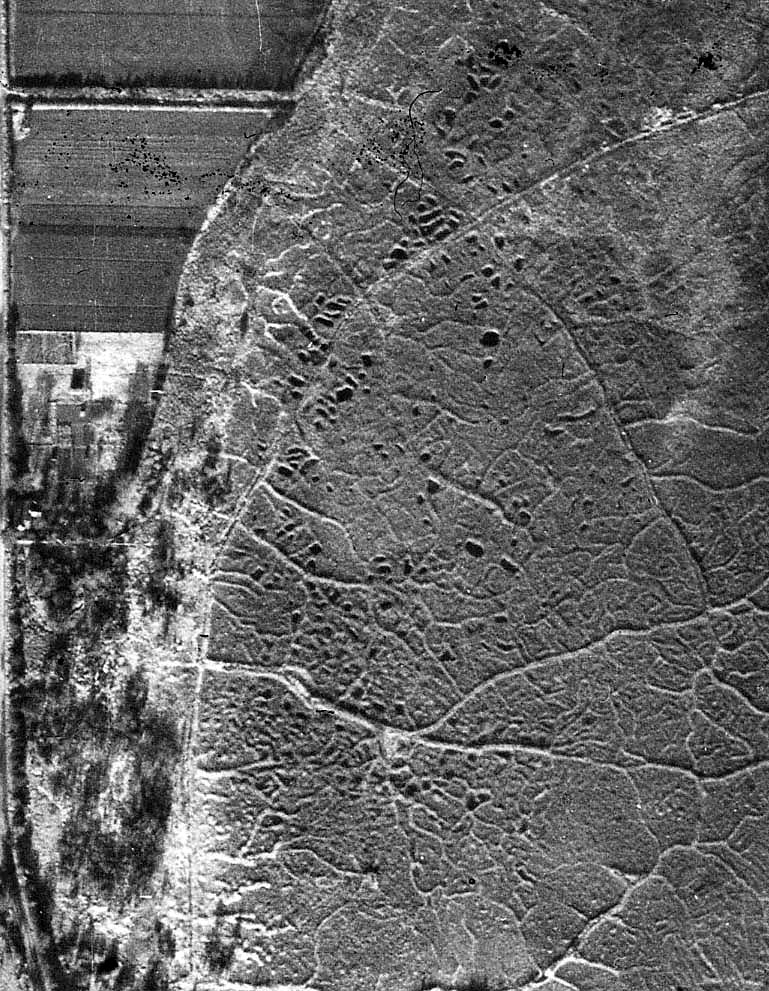

Eric Duffey's first record of Dolomedes plantarius at Redgrave and Lopham Fen was from an area of mixed fen vegetation including Schoenus nigricans Black Bog-rush and Cladium mariscus Great Fen-sedge, as well as some Phragmites australis Common Reed, that surrounded many small turf ponds (Duffey 1958). The spiders have subsequently been found to be largely restricted to open, unshaded areas of turf ponds with tussock-forming, emergent and marginal vegetation. They are rarely found in dense stands of P. australis. Much of the surface of Redgrave and Lopham Fen was pitted with, often deep, turf ponds created by peat digging for domestic fuel - a practice that probably continued until the 1930s. The dominant vegetation over much of the fen was C. mariscus; its sharp-edged but long and flexible leaves were traditionally harvested on a 4-5 year rotation to provide thatching for roof ridges.

Artesian abstraction finally ended in July 1999, at the end of a 5-year EU-funded programme to restore the fen. The restoration work involved the removal of 80 ha of scrub covering over 60% of the designated area, the excavation and removal of 36 ha of oxidized and enriched surface peat, and the introduction of an extensive grazing regime. Peat removal was mostly to a depth of 50 cm, at which nutrient levels remained low enough to support typical fen vegetation. Relocation of the bore-hole at the end of the restoration programme coincided with a series of wet seasons and resulted in rapid hydrological recovery.

Recovery of the fen's biodiversity has been a much slower process. Phragmites australis initially became dominant in and around the new scrapes, with C. mariscus only starting to reappear in many of these areas around eight years after the hydrological restoration. This was probably because high nutrient levels were maintained for a protracted period by water flushing through the remaining oxidised and degraded surface peat.

Conservation management and monitoring

1960s - 1999

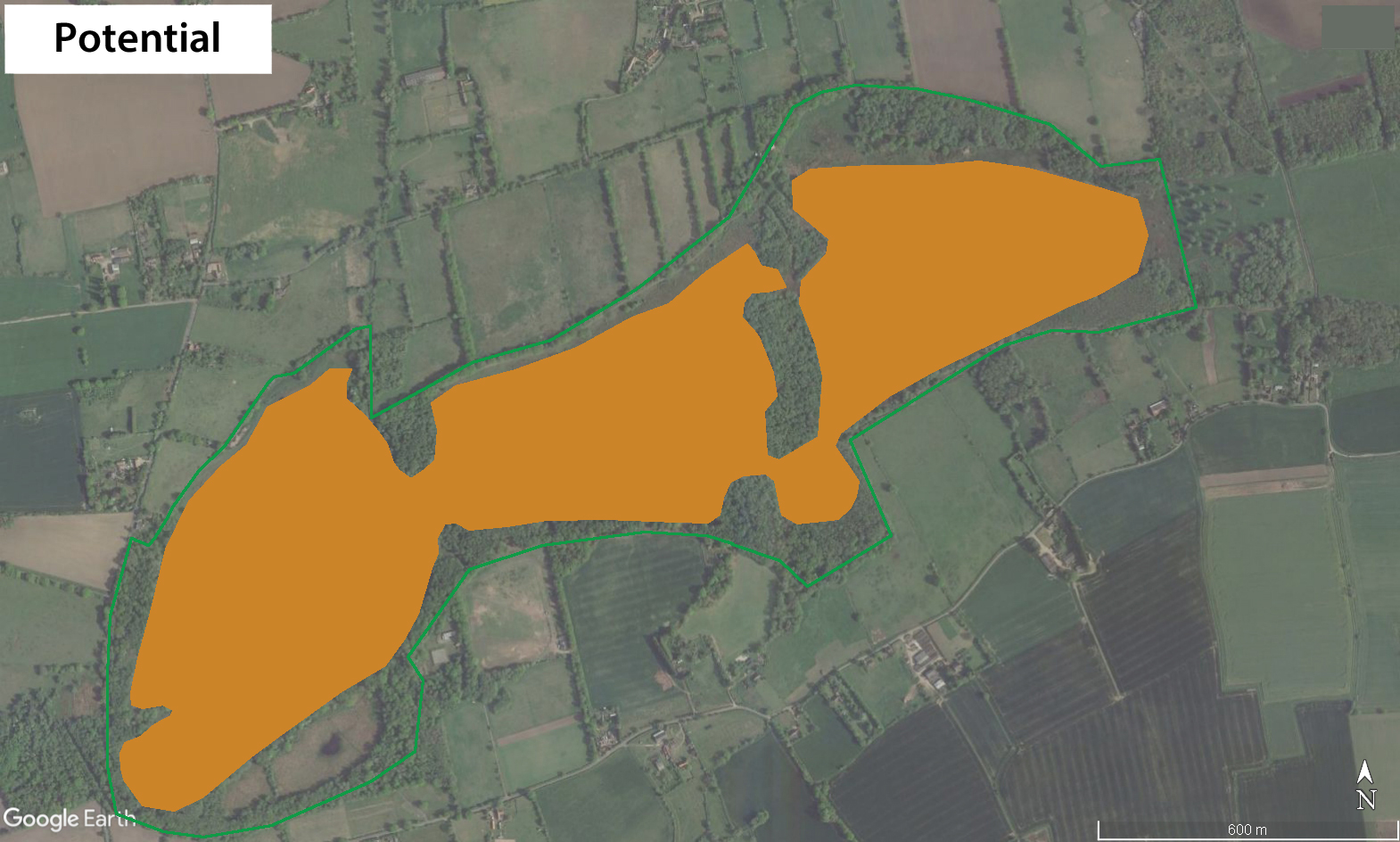

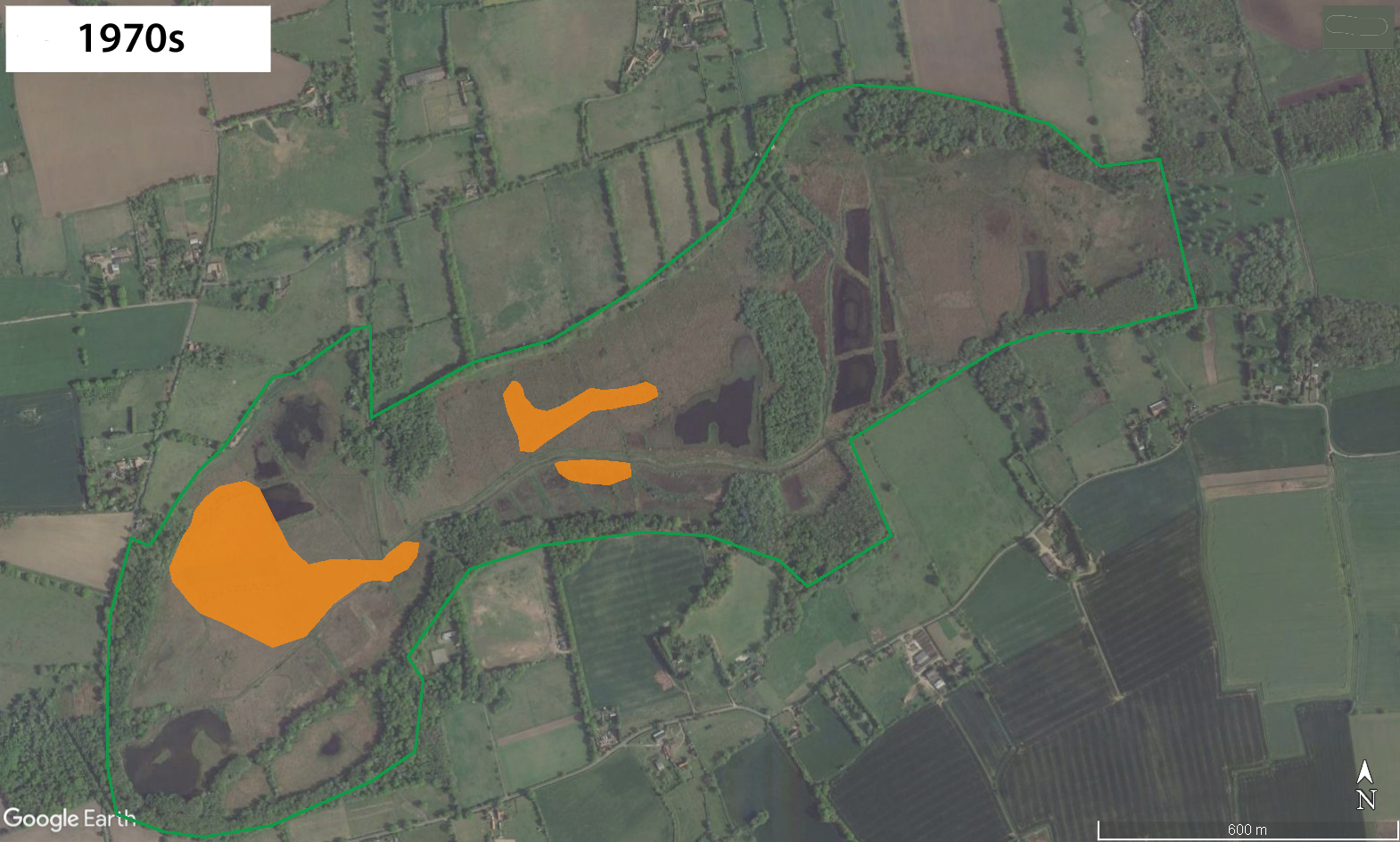

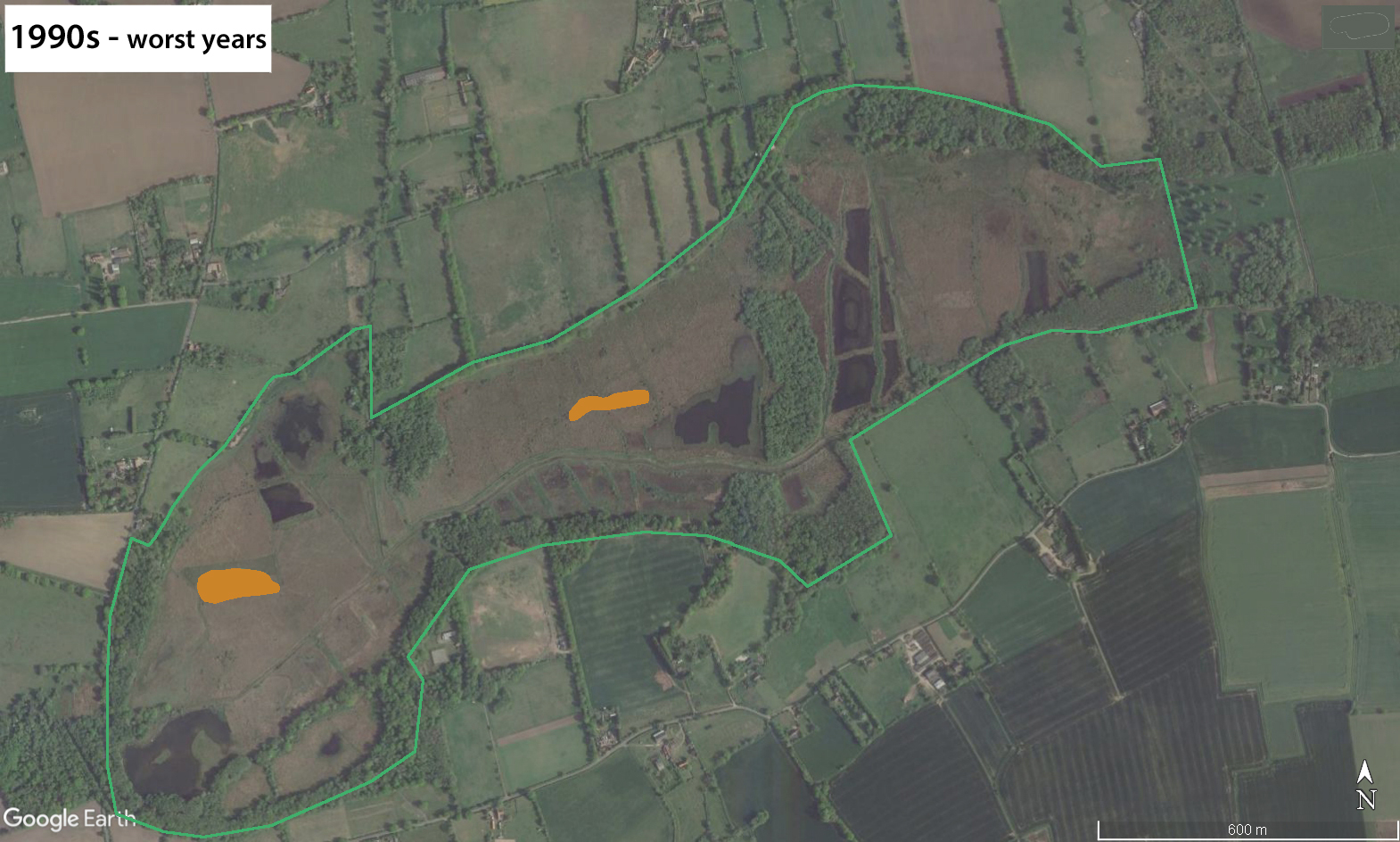

As the fen dried out, and its habitats changed, D. plantarius became progressively more restricted in range. Although no systematic survey of the extent of the population was carried out, information on the decline can be derived from collation of casual records (e.g. Thornhill 1985) and comparison with the area of the fen that must formerly have supported suitable habitat. These records show that, by the mid 1990s, the population had been lost from around 30% of the area from which it had formerly been recorded (see '1970s' map). Comparison with the area over which it is likely to have occurred in the more distant past suggests an decline of over 80% (see 'Potential' map). By the beginning of the 1990s, the population had become confined to two small enclaves, separated by a distance of ca 0.4 km and a wide belt of intervening woodland. Both of these areas were dominated by C. mariscus, growing around the margins of deep turf ponds. The depth of these turf ponds, enabling them to hold water even in dry summers, must have been a major factor in the survival of the spiders on the fen during this period.

Volunteer teams re-excavating turf ponds in the 1970s

As concern grew about the fate of the D. plantarius population in the conspicuously drying fen, additional, deep ponds were excavated. In the late 1960s and early 1970s these were hand-dug. During the late 1970s (Duffey 1977) and 1980s (Duffey 1991) many more were excavated mechanically to try to ensure a summer water supply for the spiders. Despite this, the droughts of the late 1980s left very little standing water on the Fen and D. plantarius became confined to two, small, isolated areas of deep turf ponds, on Middle Fen and Little Fen. In the notorious drought of 1976 Eric Duffey failed to find any spiders and feared that the population had been lost. He re-found them again in small numbers in the following year and increased the political pressure for action to save them.

Habitat management measures targeted at retaining the D. plantarius population during the 1990s included re-instating cutting of C. mariscus on a traditional rotation and removal of encroaching scrub. During the 1990s the introduction of extensive grazing, using a mix of Konik ponies, cattle and sheep, helped to control scrub and improved the structural variety and species richness of the more mixed fen plant associations. Additional turf ponds were excavated and existing ones deepened. The most radical measure, and probably the most important factor ensuring the survival of the population during this period, was the seasonal irrigation of ponds at the core of the two spider sub-populations (Smith 2000), a scheme jointly funded by ESW, NRA and English Nature and costing in the region of £35K.

1999-2013

When artesian abstraction ended in 1999, much more ambitious targets were set for the D. plantarius Recovery Programme. The very high potential fecundity of the spiders led to an expectation that the population might recover very rapidly.

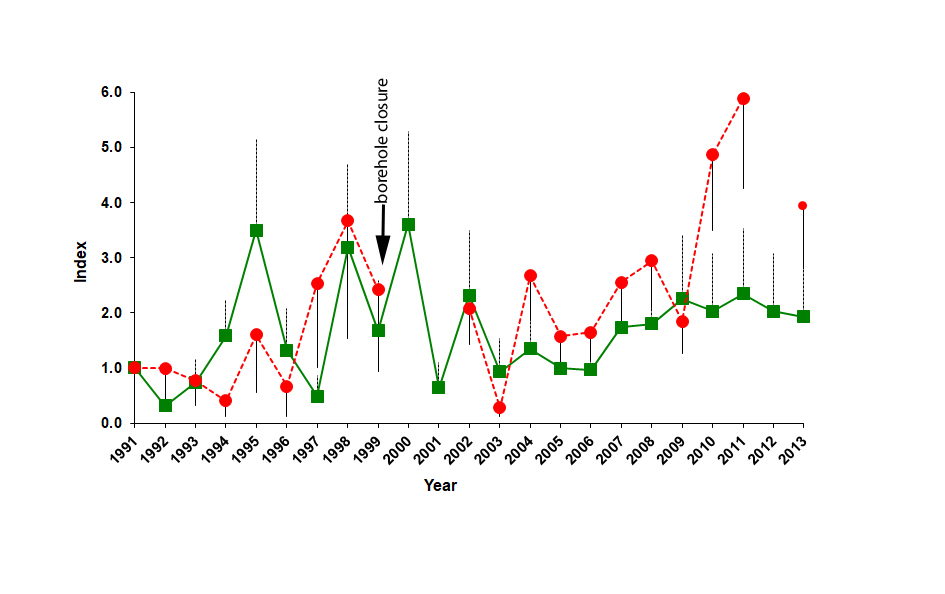

But although water levels on the fen recovered rapidly following very wet seasons in 2000/2001, systematic monitoring of the population show no evidence of any sustained or significant recovery over the 22 year monitoring period to 2013. The following graph shows the annual population indices for the two residual sub-populations of D. plantarius, on Little Fen (red line) and Middle Fen (green line), in July 1991-2013. The data are generated by a log-linear Poisson regression model plotted on a linear scale, with 2 SEs shown as positive bars for the sub-population on Middle Fen and negative bars for that on Little Fen (Smith 2000). Missing data points for Little Fen in 2000, 2001 and 2012 result from very high water levels preventing access to the survey area.

Despite the lack of movement in the population index, between 2006 and 2010 the Middle Fen sub-population expanded in range along a chain of turf ponds leading west from the core area. By 2010 the spiders had reached a series of ponds 300m away, on which they had last been recorded in 1985. This spread is thought to have been facilitated by a combination of improvement in vegetation quality, together with a relatively long series of summers in which these ponds retained water. At the eastern end of the Middle Fen core area, another new chain of turf ponds, dug in 2009, was colonised in 2012.

In addition to this natural increase in range, in 2011 and 2012 spiderlings of Redgrave and Lopham Fen provenance were introduced to an area of the fen with very suitable habitat (Great Fen) but from which the spiders had not previously been recorded. This translocation formed part of the wider translocation programme for D. plantarius.

2014 onward

Since 2014 there have been many changes in the Redgrave and Lopham Fen D. plantarius population and in its conservation management. For the most-part these have been very positive, with a substantial increase in range brought about in part by natural colonisation of recently-excavated scrapes and ponds, and in part by the establishment of a third focus of population by translocation.

The main habitat management directly targeted at Fen Raft Spiders continues to be a rolling programme of turf pond creation and re-excavation, to maintain standing water in dry summers and to extend the area of summer-wet links between the core areas of turf ponds. Vegetation management continues to involve cutting of mature stands of C. mariscus together with extensive, mixed grazing and periodic scrub removal.

The standardised cenus method used since 1991 was finally ended in 2014 for a number of reasons, including:

- the increasing aerial extent of the population required a substantial expansion in the search area, making the very labour-intensive searches from within the water impracticable

- the ending of core funding for Natural England necessitated a method more appropriate for volunteers than working from within the water

- safety issues around working within the increasingly deep silt and dense mats of Charophytes (Stoneworts) within the ponds were becoming significant; several ponds included in the annual census could not longer be searched in this way

- the spider's expanding range, and first signs of recovery in its numbers, made possible for the first time a monitoring method based on its conspicuous nursery webs. This method would not have produced sufficiently robust data at an earlier stage in the project when nursery web numbers were very low and the area of occupancy of the spiders very small. As well as being more practicable at this stage in the project, it has the additional advantage of greater comparability with the monitoring on the grazing marsh sites (Pevensey Levels and New populations)

- the need to extend the census to include Great Fen, where spiderlings were translocated to establish additional sub-populations in 2010-12 (above).

The new census methodology developed since 2014 has two separate elements. One involves regular counts of nursery webs, made at weekly intervals throughout the breeding season, along transects over a much wider area of the fen than the old survey. The gain in spatial information is inevitably accompanied by a loss in sensitivity to population changes between years, although the numbers of nurseries now encountered are sufficient to give a reasonable picture.

The second monitoring tool comprises a one-day count made by a large team of volunteers, as far as possible in all potential habitat throughout the reserve; a single survey of this kind had previously been conducted in 1994. The primary purpose of this is to assess changes in the spider's range that cannot be detected by the existing transects; it is not expected to yield robust data on spider densities across the fen. This survey was started in 2019 but could not be resumed until 2021 because of COVID-19 restrictions.

Although it has proved difficult to find volunteers to deliver consistent monitoring over such a wide area and sustained period of the year, with only one of the weekly transects monitored consistently each year, the new methods are starting to deliver valuable results.

The transects show that the new population created by translocation on Great Fen was well established by 2015-2017. On Middle Fen the spider's range increase has continued, with breeding recorded consistently over a wide area. The monitoring is starting to give a good picture of population trends throughout this area, with summer water levels likely to be the main factor driving changes in density. Nursery counts on the Middle Fen transects were around 200 in 2019 but fell by two thirds in 2020 following protracted droughts immediately after the first spider broods in 2019 and them in spring and in summer 2020.

The fen-wide, one day survey in 2019 revealed, for the first time, colonisation of several of the large scrapes created on the fen during the restoration operations in the 1990s (see map below). These scrapes were initially colonised by P. australis but this has been progressively displaced by C. mariscus which provides much more suitable habitat for the spiders. Breeding densities on these scrapes appear to be low but progressive colonisation of them all could increase the spider's range on the Fen by up to 22.5 ha.

*Natural England absorbed the functions of English Nature in 2006.

Summary reports and papers on the status of D. plantarius at Redgrave and Lopham Fen:

Doleman, P. M. 1991. Dolomedes Species Recovery Programme: analysis of water chemistry from Lopham Fen. Unpublished report, English Nature*, Peterborough.

Duffey E. 1958. Dolomedes plantarius Clerk, a spider new to Britain, found in the upper Waveney Valley. Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society: 18:1-5.

Duffey, E. 1960. A further note on Dolomedes plantarius Clerk in the Waveney valley. Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists' Society 19, 13-176.

Duffey, E. 1977. World Wildlife Fund helps Dolomedes plantarius. Newsletter of the British Arachnological Society 17: 12.

Duffey, E. 1991. The status of Dolomedes plantarius on Redgrave and Lopham Fens 1991. Unpublished report to English Nature, Peterborough.

Kennet, J. A. B. 1985. Report on the ecological status of Dolomedes plantarius on Redgrave and Lopham Fens. Unpublished report, Suffolk Wildlife Trust, Ashboking.

Smith, H. 2020. The Fen Raft Spider – from unknown past to uncertain future. British Wildlife 32: 98-109.

Smith, H. 2018. Hanging by a thread: Norfolk’s rarest spiders. Transactions of the Norfolk and Norwich Naturalists’ Society 51: 1–14.

Smith, H. 2015. Report on the Fen Raft Spider Dolomedes plantarius translocation project in 2014. Unpublished report to the Fen Raft Spider Steering Group partners.

Smith, H. 2014. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2013 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2013. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2012 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2011. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2011 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2010: Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2010 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2009. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2009 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2008. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2008 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2007. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2007 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2006. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: 2006 summary report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2005. Fen Raft Spider Recovery Project: Report for Redgrave and Lopham Fen 2001-2005. Unpublished report to Natural England.

Smith, H. 2001. The Fen Raft Spider recovery project: a decade of monitoring. English Nature Research report No. 358, English Nature, Peterborough.

Smith, H. 2000. The status and conservation of the fen raft spider (Dolomedes plantarius) at Lopham and Redgrave Fen NNR, UK. Biological Conservation 95: 153-164.

Smith, H. 1998. Fen raft spider project: interim summary report for 1998. English Nature Research Report No. 299.

Smith, H. 1997. Fen raft spider project: interim summary report for 1997. English Nature Research Report No. 258.

Smith, H. 1996. The status and management of Dolomedes plantarius on Redgrave and Lopham Fen National Nature Reserve in 1996. English Nature* Research Report No. 214.

Smith, H. 1995. The status and management of Dolomedes plantarius on Redgrave and Lopham Fen National Nature Reserve in 1995. English Nature* Research Report No. 168.

Smith, H. 1994. The status and management of Dolomedes plantarius on Lopham and Redgrave Fen National Nature Reserve in 1994. Unpublished report to English Nature*, Peterborough.

Smith, H. 1993. The status and management of Dolomedes plantarius on Lopham and Redgrave Fen National Nature Reserve in 1993. Unpublished report to English Nature*, Peterborough.

Smith, H. 1992. The status and autecology of Dolomedes plantarius on Lopham and Redgrave Fen nature reserve in 1992. Unpublished report to the Suffolk Wildlife.

Thornhill, W. A. 1985. The distribution of the great raft spider, Dolomedes plantarius, on Redgrave and Lopham fens. Transactions of the Suffolk Naturalists' Society 21: 18-22.